On Sichuan Pepper

Taste the tingle, know the tingle, rejoice in the tingle.

In the 2019 edition’s entry on garlic, we wrote “garlic just makes life better,” and I stand by that. I can’t remember a time I ever regretted adding garlic (or more garlic) to something. I know many home cooks feel the same way.

And yet, we have little choice in the garlic we buy. Despite the existence of ten types of garlic and hundreds of cultivars, most supermarkets just sell “garlic” with absolutely no hint at what type of garlic it is.

Whether you could tell the difference between types once the garlic has been simmered into marinara, sautéed up with spinach or chard, or roasted inside a chicken is an open question. But given the seemingly universal love of this smelly bulb, garlic’s simultaneous ubiquity and genericness has always interested me.

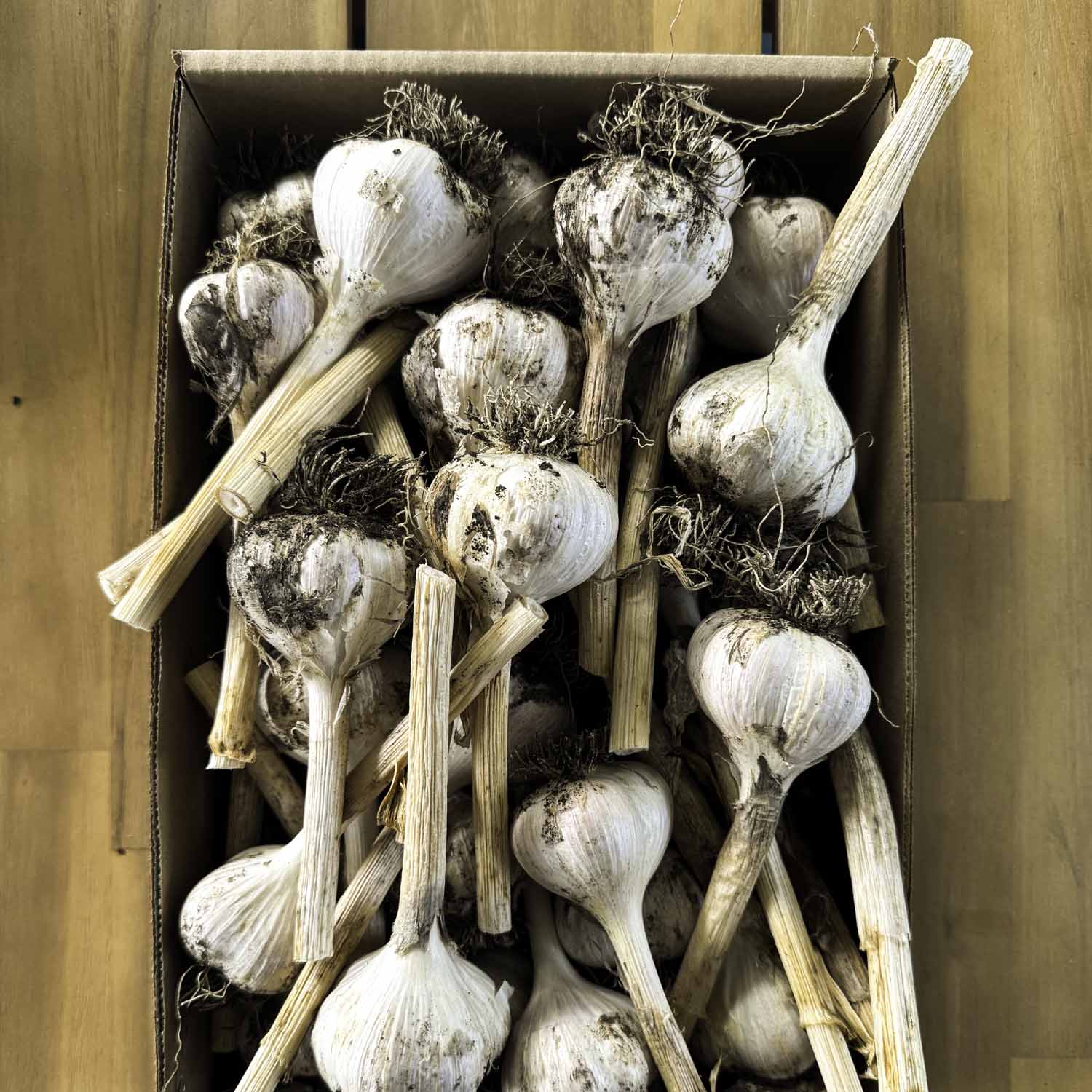

When I started growing garlic myself, some of the pieces (cloves?) began to fall into place. I learned that there are two main categories of garlic under which all types and varietals are classified: hardneck and softneck.

Hardneck garlic produces a secondary crop of garlic scapes (also called garlic whistles or garlic whips), and while it doesn’t store as well as softneck garlic, it often produces larger heads with larger cloves. Softneck garlic doesn’t produce scapes and has smaller cloves, but lasts longer in storage.

I am not able, with my small urban yard, to grow and store all the garlic I might use in a year, so I plant hardneck garlic because I love garlic scapes and I appreciate larger cloves of garlic (larger cloves = less time peeling tiny, fiddly cloves). I’ve yet to have hardneck garlic go bad on me before I use it all, even though it’s supposedly inferior in storage (I imagine this matters more if you are genuinely trying to grow 100 percent of the garlic you need).

If you buy garlic at a farmer’s market, it’s likely the grower will know the variety (and certainly whether it is hardneck or softneck). Softneck garlic is the kind we find most in supermarkets. While it’s reliable, I know I’m not the only one turned off by trying to peel a normal-looking clove only to have it split into five or six diminutive ones. What is this? Garlic for ants?

You may also run into green garlic at the farmer’s market, which is harvested before the individual cloves form. Some green garlic, like that pictured above, is harvested so young that the bulbs have yet to form, resembling tiny, slender leeks or sturdy looking scallions. Sometimes green garlic will be harvested when the bulbs have formed but the skins separating the cloves are still pliable and moist, not dry and papery (it will often look like one large clove when you peel it). While green garlic is more tender and mild than mature garlic, you use it much the same.

Elephant garlic is actually an impostor, not a type of garlic at all but rather a type of leek. Despite its size, which might lead you to think that it will be spicy and strong, elephant garlic is very mild, though it can be used, you guessed it, just like normal garlic. For those who don’t appreciate raw garlic’s pungency, elephant garlic would be a nice stand-in for raw preparations like salsa, pesto, and salad dressings.

When I buy garlic at the grocery store, I gently but firmly squeeze the heads. A little give is normal, but the garlic should be firm. Note any cloves that seem dented through the skin—this means they are likely either rotten or on their way. Sprouting garlic is nothing to be afraid of in the kitchen, but I avoid buying heads of garlic that are already sprouted in the store. This means the garlic has been sitting around for a long time and is likely not at its best.

Speaking of sprouted garlic, when I’ve kept garlic around for a little too long and green shoots start to emerge, I treat the garlic one of two ways. If I’m using the garlic raw, I cut the cloves in half and remove the green shoots. If the garlic is bound for cooking, I don’t bother, and I chop up the garlic shoots and all.

Store cured garlic at cool room temperature, away from direct sunlight, heat, and moisture. Air should be able to flow around the garlic for optimum storage. I keep my garlic in one of those hanging produce baskets.

There are a few ways to quickly peel garlic cloves, and the best method depends on how you plan to use the garlic. To peel a large quantity of cloves at once, provided you do not need all the cloves to be perfectly whole, separate the garlic into cloves, put them in a plastic quart container (really any food storage container with a tight-fitting lid will do), and shake the heck out of them. The papery skins will come off easily, though some of the cloves may be broken or slightly bruised.

If you want to be sure your garlic stay whole—for, say, grating with a microplane, or using in a dish that calls for thinly sliced or whole cloves—you can hold each clove between your thumb and index finger so that your thumb is pressing on the root end and squeeze firmly. Depending on your finger strength and the freshness of the garlic, you may need to push the clove downward on your cutting board or use your other hand to help squeeze. The garlic skin will split open, giving you an easy entry to peel off the skin. (If a clove is especially stubborn, press on the flat sides to loosen up the skin and try again.)

Finally, if you’re ultimately going to be chopping or mincing the garlic, just smash the clove with the side of your knife. The skin will come right off, and the garlic is already on its way to being roughly chopped.